The Neverending Story

15,374 days.

That’s how long it’s been. Some days it snows and some days the sun burns your skin as you wait for your bus and some days Presidents are impeached and some days, some glorious, magical days, fate smiles upon you and yours and leaves you the ultimate champion. Jerry Sloan is waiting for that day.

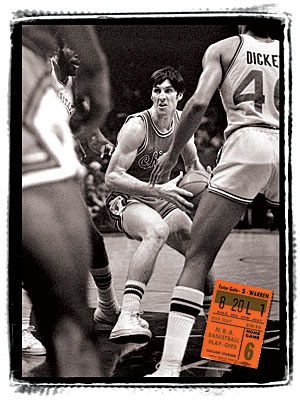

See, Sloan is a lifer. He has played or coached NBA basketball for 42 years, but given his tenacious preparation and pugnacious disposition, he appears to still be scrapping for his first taste of success. He was drafted (twice, actually) by the Baltimore Bullets, before they became the Washington Bullets, and later the Washington Wizards (the original name fit best). He began his rookie season on October 16, 1965 with a 133-101 loss to the Philadelphia 76ers. The game’s leading scorer was a 29 year old by the name of Chamberlain. It wouldn’t be the first time Sloan tasted defeat at the hands of an all-timer.

It is exceedingly easy to overlook Jerry Sloan in the annals of great coaching. He has toiled in anonymity for decades, in pre-MJ Chicago, in Salt Lake City, neither a hoops hotbed. His playcalling has been derided as simplistic, overly reliant on a defense with bumping man-to-man physicality and an offense revolving around a basic pick and roll. In the era of the “players coach” whose ego-massaging and media-pacifying qualities are almost more important than Xs and Os, Sloan doesn’t give a damn, repeatedly questioning (publicly and privately) his players’ tenacity, dedication, and manhood. This is not fair; with himself as the measuring stick, no other player can come close. The one fact that the most people overlook is this: Sloan has coached for 22 seasons and has a .600 regular season winning percentage. That’s just about 50 wins a year, every year. Forever.

Sloan has never been voted Coach of the Year.

He doesn’t belong to today. He’s in the crusty Dick Williams/Vince Lombardi/Don Cherry (albeit less flamboyant) mode, just as likely to swallow his whistle while screaming as applaud a good play. Some of his players today, such as rising star point guard Deron Williams, have responded well and matured over the seasons. The mercurial jack of all trades Andre Kirilenko, on the other hand, has not, looking lost and disoriented on the court. Sloan’s my way/highway style isn’t for everyone, and there are certainly logical detractors for his occasionally vicious remarks and brutal practice atmosphere. He’s not a coddler, nor sometimes even likable. But for those with thick enough skin to run through the fire, it works.

Certainly no pundit could predict the Jazz’s resurgence last season. Sloan’s streak of 15 consecutive postseasons (20 for the team) ended in 2003-04 and the ’05 Jazz bottomed out at a pitiful 26-56.  By the next season, after acquiring Williams via the draft and signing a surprising center, the 18 and 9 nightly Mehmet Okur, the Jazz had recovered to 41-41, ending cries that without Stockton-to-Malone the game had passed Sloan by. A healthy season from banger Carlos Boozer

By the next season, after acquiring Williams via the draft and signing a surprising center, the 18 and 9 nightly Mehmet Okur, the Jazz had recovered to 41-41, ending cries that without Stockton-to-Malone the game had passed Sloan by. A healthy season from banger Carlos Boozer  followed, and last year the Jazz were one of the NBA’s big surprises. Their offense ranked 15th in pace factor, but the brutally efficient frontcourt, backed by Williams, Matt Harpring, and Derek Fisher with gas still in his tank finished third in the league in points. Utah won 51 games and Sloan accepted his praise the way he always does: grudgingly. “Nobody cares what you did yesterday. Life is pretty simple when you look at it that way,” said Sloan, discussing his team’s postseason prospects. Of the young stars he quipped, “Freshmen in high school don’t know what’s going on.” The Jazz won 7 home playoff games in a row before eventually bowing out to the eventual champion Spurs in the Western Finals.

followed, and last year the Jazz were one of the NBA’s big surprises. Their offense ranked 15th in pace factor, but the brutally efficient frontcourt, backed by Williams, Matt Harpring, and Derek Fisher with gas still in his tank finished third in the league in points. Utah won 51 games and Sloan accepted his praise the way he always does: grudgingly. “Nobody cares what you did yesterday. Life is pretty simple when you look at it that way,” said Sloan, discussing his team’s postseason prospects. Of the young stars he quipped, “Freshmen in high school don’t know what’s going on.” The Jazz won 7 home playoff games in a row before eventually bowing out to the eventual champion Spurs in the Western Finals.

It would be the sweetest victory for Sloan. During all 42 years of his professional career he has never been a champion. The closest he came was in 1997 and 1998, with two exceptional Jazz teams denied the pinnacle by a Chicago dynasty. The ’97 team lost to a 69 win Bulls team, taking a tough Game Five defeat from a exhausted, flu-ridden Michael Jordan and falling two days later. With home court and 62 wins in 1998, the Jazz lost three Finals games by a combined total of ten points. The very Bulls he put on the map as their first expansion draft pick (he was known as “The Original Bull”) concluded their parade through the 90s by ripping out their ancestor’s organs.

denied the pinnacle by a Chicago dynasty. The ’97 team lost to a 69 win Bulls team, taking a tough Game Five defeat from a exhausted, flu-ridden Michael Jordan and falling two days later. With home court and 62 wins in 1998, the Jazz lost three Finals games by a combined total of ten points. The very Bulls he put on the map as their first expansion draft pick (he was known as “The Original Bull”) concluded their parade through the 90s by ripping out their ancestor’s organs.

The heart and soul took a few more years. First the team lost John Stockton and Karl Malone after the 2003 season, the duo that defined the face of a franchise more than any in sport. Whether 1986, 1993, or 2002, Sloan could diagram the play.  The one comes weak side. Four comes up from the block and sets a high screen at the elbow, picks one’s defender. Once separation occurs, roll towards the hoop. One can shoot or pass. Allegedly it’s called the pick and roll, but everyone knows the real name is Stockton to Malone. Suddenly, Stockton and Malone were gone, and so was Utah’s A-listers, its whole franchise. Only four years later, with Boozer and Williams the present combo, has the Delta Center come alive again, its fans now recognizing and praising the new blood. In fact, only Sloan remains from those previous times; hell, he’s still a link to the Jeff Malone era.

The one comes weak side. Four comes up from the block and sets a high screen at the elbow, picks one’s defender. Once separation occurs, roll towards the hoop. One can shoot or pass. Allegedly it’s called the pick and roll, but everyone knows the real name is Stockton to Malone. Suddenly, Stockton and Malone were gone, and so was Utah’s A-listers, its whole franchise. Only four years later, with Boozer and Williams the present combo, has the Delta Center come alive again, its fans now recognizing and praising the new blood. In fact, only Sloan remains from those previous times; hell, he’s still a link to the Jeff Malone era.

While the Jazz struggled with finding their team identity, Sloan himself received a far crueler beating later in 2004, when Bobbye, his wife of 41 years, succumbed to a seven year battle with cancer. The pancreatic cancer which took her away was wholly different from the breast cancer she fought after her diagnosis in 1997. Sloan barely made it through the season, coaching only on Bobbye’s wishes. After she died, he nearly quit the game that gave him life for his adult life. He pressed on, eventually. It was what he knew, what made him a man. And though in interviews his voice still softens when recalling Bobbye, late last year he married Tammy Jessop, a single mother in the Salt Lake area.

With his most major issues finally manageable and a year back at the top under their belts, the coach and his cohorts have set dead aim at the Larry O’Brien trophy. This season the Jazz are 7-3 and running away with the Northwest Division. Deron Williams is averaging 19 points and 9 assists a game, a lock for the West All-Star team. The team as a whole is shooting 49% from the field, and though there are doubts about the team’s perimeter defense, ESPN’s Marc Stein and Ric Bucher both put Utah on the short list of viable potential champions. While the Western Conference is much more difficult and treacherous a path than the moving platform glide back East, the Jazz could easily roll through a weak division and secure a solid #2 seed. Okur is the oldest starter at 28; there’s a darn good chance that the young legs will still be fresh against the champs. San Antonio’s maturity is its blessing and its curse; the first title of the Parker/Ginobili era came while Stockton and Malone still ran the pick and roll. The new blood is on the precipice.

is averaging 19 points and 9 assists a game, a lock for the West All-Star team. The team as a whole is shooting 49% from the field, and though there are doubts about the team’s perimeter defense, ESPN’s Marc Stein and Ric Bucher both put Utah on the short list of viable potential champions. While the Western Conference is much more difficult and treacherous a path than the moving platform glide back East, the Jazz could easily roll through a weak division and secure a solid #2 seed. Okur is the oldest starter at 28; there’s a darn good chance that the young legs will still be fresh against the champs. San Antonio’s maturity is its blessing and its curse; the first title of the Parker/Ginobili era came while Stockton and Malone still ran the pick and roll. The new blood is on the precipice.

If the Jazz don’t win the NBA Championship this season, it won’t be anything new. They’ve never done it in their history, and they are neither the favorite nor even a chic pick to ascend the mountain. But if they do stumble, it won’t be because of their coach, a man who has lost so much that it makes his victories incomparably sweet. Certainly the new Big Three in Boston and the powerhouse Texas Trio continue to gobble up headlines, rolling through more ink than a fleet of squid. That’s a-okay with Jerry Sloan, bandleader of yet another stellar Jazz ensemble. You’ll never see him as the first trumpeteer, nor the lead singer of praise. Rather, he’ll just keep playing in the background until he gets it right. The song remains the same.

Day 15,375 begins.